Cultural participation policies: A poverty of ambitions

Dr David Stevenson talks about audience diversification, confronts the dominant hierarchy of cultural activities, and looks to create space for valuing everyone's chosen cultural experiences the same way.

This series of articles was commissioned in preparation to the IETM Plenary Meeting in Rijeka, 24-27 October 2019, focusing on the theme Audiences. The debate aims to challenge the most common assumptions and beliefs regarding this broad and complex subject and to bring fresh ideas and alternative approaches to it.

In many countries it is not unusual to hear of cultural organizations attempting to diversify their audiences by reaching out to those who are often described in English as “non-participants” or “non-attenders.” While some organizations may undertake this work of their own volition, for many it responds to the implicit or explicit expectations of their funders.

To date, much of my research has focused on trying to understand who or what a “cultural non-participant” is. I have reached the conclusion that not only do they not exist, but also that the continued use of the term helps preserve an inequitable status quo, which can never deliver the equity that’s central to the existence of a cultural democracy—something many people in the cultural sector tell me they, too, are committed to achieving.

I do not doubt there are many people who welcome support to help them take part in cultural activities offered under the guise of “outreach” and “engagement.” The barriers these individuals face are real and the personal benefits they gain through their participation are surely genuine. However, not all people want to take part in the activities on offer, nor should they have to.

It is important to make a distinction between those who express an interest or desire in doing something but are hindered to some degree and those who have expressed no interest or desire and identify no absence in their life because of it. Being prevented from doing something you want to do because of tangible barriers such as lack of transport or finance is not the same as choosing not to do something you have no interest in, place no value on, would gain no unique utility from, and which may even have a detrimental effect through the loss of opportunity to spend that time doing something you value more.

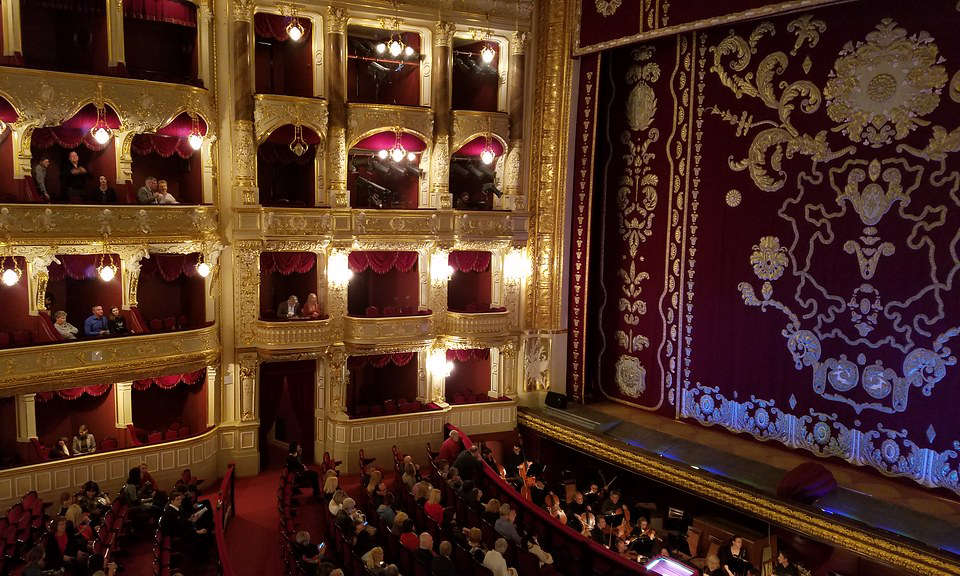

This matters because the societies we live in are not equitable, and there are differences in the degree to which individuals are free to pursue their own cultural interests and desires. Relative poverty, lack of time, and geographic location are just some of the factors that potentially limit an individual from exerting their agency with regard to the way in which they pursue and enact their cultural values. It doesn’t matter if it is the opera, a Kylie Minogue concert, a ticket to the latest blockbuster, or a visit to an art exhibition, if you have no access to transport, no disposable income, or a long-term health condition, you may struggle to “participate” in the ways others take for granted.

However, the concern within cultural policy for facilitating cultural participation does not generally extend to helping people overcome such barriers irrespective of the activity in question. While many working in the cultural sector may be uncomfortable to admit it publicly, their actions suggest that there remains a dominant hierarchy of cultural activities, in which some forms are assumed to be of greater value to participants than others. While this hierarchy may be more implicit than perhaps it once was, it is arguably all the more insidious because of this. It remains the case that those who are the most economically and socially deprived must, more often than not, accept the mediation of cultural experts and professionals in deciding what will be of most value to them if they want to benefit from any support to “take part” in culture. If your cultural interests are not in alignment with what these professionals believe you should value then any barriers you may face in cultural participation activities on the open market is your problem alone.

Of course I want any place, space, or activity that receives public money to be unequivocally welcoming to anyone and everyone. However, I equally respect someone’s right to say that what is on offer is not for them. We all do it—I can give you a whole list of activities that are not for me—but when certain people say this about the type of cultural activities and organizations that most commonly receive the greatest subsidy, the immediate response is all too often to question their judgment and assume their lives would be better if only they would change their mind and their cultural preferences.

Yet our sense of self is arguably informed as much by what we choose to forgo as by what we choose to partake in. Just because someone says that the theatre is “not for them” does not mean there is no another activity by which they already derive equivalent benefits to that which a theatre lover gains from going to a performance. As such, it is legitimate for such a person to ask why the state is willing to subsidize and support the cultural interests of some but will dismiss the cultural interests of others as discretionary luxuries.

In my conception of a cultural democracy, no cultural experience should be valorized over any other, and what would be celebrated would be the ever-increasing multiplicity of ways all citizens can actualize their cultural values without devaluing or disrespecting what someone else wants to pursue. The feelings, emotions, and benefits that one person experiences from watching the latest Netflix box set, going to their local pub to take part in karaoke, constructing a new world in Minecraft, or knitting at home listening to the radio should not be seen as any more real or valuable than what someone else may experience from going to the ballet or taking part in life drawing classes. I do not need to enjoy going to football matches to recognize that others value it in the same way I value going to the cinema. I can see that gaming means as much to some people as reading means to me. I have no interest in going to live music concerts but I think that it is as important that someone can go to the Spice Girls reunion tour as it is that they can go to see the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra.

Some will disagree with me, which is a legitimate position to take. However, I find it hard when I hear these same people accuse others of failing to “value culture” when there are numerous cultural activities they apportion little value to themselves. I find it frustrating that those in the cultural sector who believe in a cultural hierarchy are often reticent about making their beliefs explicit. I find it even more frustrating that some of these people also claim to support the aspirations of a cultural democracy; for a cultural democracy is not compatible with the somewhat Orwellian assertion that although all cultural participation is equal, some is more equal than others.

In my conception of a cultural democracy, it should not be the job of cultural professionals to regulate the legitimate ways in which a valuable experience can take place. As cultural commentator John Holden has argued in Culture and Class, “No one should be excluded from any sort of cultural activity, but more importantly, as a matter of social justice, nor should they be excluded from helping to define what culture means.” Cultural participation is a process of individual judgment and gradual curation through which we identify and prioritize the sites and activities that bring us the greatest pleasure and greatest value. Of course people should be encouraged to try new things, but this goes for all of us—not just those who have no interest in theatres, museums, or opera houses.

The argument that “non-participants don’t know what they don’t know” is often used to justify why someone’s disregard for a particular type of activity should not be accepted as a legitimate expression of personal taste. However, this is a redundant statement—who among us knows what we don’t know? How do the opera lovers know that their lives would not be better if they stopped going to opera and started livestreaming gaming on Twitch? When I spend my Sunday in the National Gallery of Scotland, how do I know that my life would not be transformed if, instead, I found a community line-dancing group to join? And, more pertinent to my current argument, why does no one care about questioning the cultural participation choices that I make as an educated middle-class white man?

I believe this is because there are certain people whose cultural judgments are framed within cultural policy as being flawed by default. Consequently, such individuals are assumed to need reorienting towards what are tacitly accepted by the majority of those working in the subsidized cultural sector as distinctly different and ultimately more valuable types of cultural experiences than those these individuals may already be choosing to take part in. Yet such assumptions question, to the point of denial, the capacity of those labelled as “non-participants” to both think and feel for themselves about what forms of activity they value as a meaningful cultural experience.

While there has been increasing rhetoric around the importance of diversity in the cultural sector, this has tended to focus on diversifying the audiences for certain types of cultural activity rather than diversifying the types of cultural experience that are recognized, celebrated, and supported as being of value. To diversify policy in this manner would require us all to recognize the right of individuals to legitimize an experience as culturally valuable on the basis of its affect on them alone and to acknowledge that apparently disparate activities share the potential to afford similar benefits to different people.

As philosopher Jacques Rancière has argued, equality should not be understood as an end game; it is not something that is to be granted or provided via the successful delivery of certain actions or interventions by those who already believe themselves to have it. It is something each individual has the right to assert and to have acknowledged without question. True equality requires—and indeed must remain—fully independent of any social mediation. If every action starts from the affirmation of equality then it is equity that must be delivered. As such, there is a moral imperative for any state claiming to embody the ideals of a progressive democracy to ensure that everyone has the capabilities, the time, and the right to express and pursue their own individual and collective cultural values.

In this case, what becomes most problematic is not that one person does not apportion the same value to the ballet that another does, but that the cultural values of one individual or group are given greater privilege than the cultural values of another. That for some, the activities, organizations, and objects they value most could, for various reasons, be increasingly inaccessible to them, yet this would not be understood as a problem to which the resources of the state can, or should, be applied. If cultural policy is to help address social injustices and to avoid reinforcing existing inequities, it must be concerned with creating the conditions in which everyone can express themselves freely and in the manner they perceive to be most valuable. For being able to do so is an indicator of freedom and an expression of power.

However, this will not be achieved through the type of incremental tinkering to policy actions, short-term projects, flawed evaluations, and futile arguments over relatively small pots of funding, which have become the hallmark of contemporary cultural policy. Indeed, a cultural democracy—based on the affirmation of equality and committed to ensuring equity of support—cannot be achieved through cultural policy alone. It requires changes to social and economic policy and for diverse and equitable cultural participation to be seen as the evidence of an equal and inclusive society rather than a tool to help achieve it. Such fundamental change will require revolution, not evolution. Cultural policy in many countries is constrained by a dependency that stretches back to the European Enlightenment and one that is imbued with the logics of hierarchy and distinction. It is this that needs to be “transformed,” not the people who are labelled as “non-participants.”

However, the state of financial precarity a large number of organizations and artists permanently function in means that although many bemoan the instrumentalization of their creative practice by governments and funders seeking to “fix” social and economic problems, they are arguably complicit in sustaining the status quo by using it to maintain and/or advance their own careers. The current economic landscape in many countries engenders the need for such self-serving tactics and, in so doing, fails to create the conditions for truly radical new ideas to emerge. I would like to see cultural policy focusing on creating the conditions in which these ideas can arise and urge those who believe in the importance of cultural democracy to commit to challenging every assumption upon which the status quo is based, even where this may weaken our own status and privilege.

For why limit ourselves to asking how a restricted number of organizations can be more supportive of cultural participation (for what will always be a relatively small number of people), when we could be asking how to create a society that is more supportive of everyone’s cultural participation. Let’s stop trying to “evidence” what value cultural participation has for the economy, or education, or health, and start demanding evidence of how our economy, our education system, and our health service can better deliver a society where we are all able to spend more time doing what is culturally valuable to each of us. Let’s accept that everything isn’t for everyone and never will be, but that there should be something for everyone. Let’s not waste time judging one cultural experience against another; instead, let’s wonder at the fact that each of us can find similar joy and meaning in such apparently different objects and activities. Let’s affirm equality of sensibility for every person and an abundance of cultural desire rather than a deficit of cultural interest.

None of this will be easy or straightforward, but if we redirect our collective attention from trying to explain why people don’t do certain things to thinking about how we can make meaningful structural changes to better support them in pursuing the things they do want to do, maybe we won’t still be having the same debates in twenty years. Hopefully, we will all be too busy participating in cultural activities that give our lives meaning.

This article was originally published on Howlround on the 8th of October 2019. Read the original article.

|

|

Dr David Stevenson is Head of the Division of Media, Communication and Performing Arts at Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh. Drawing on his academic research alongside 10 years of management experience in the public and private sector, David teaches at both undergraduate and postgraduate level in the fields of Arts Management and Cultural Policy. David has a PhD in Cultural Policy, an MA (Distinction) in Arts and Cultural Management, and a BA (First Class) in Art History. His research is primarily concerned with the strategic management of cultural organisations and widening participation in cultural policy processes. |