How to make our performing arts practice more ecologically sustainable?

Seven lessons learnt during a brainstorm at the IETM Plenary Meeting in Rijeka (24 October 2019)

Last week we were in Rijeka with some 350 performing arts professionals for the IETM Plenary Meeting, the international network for contemporary performing arts. With my new IDEA Consult hat, I animated a workshop for the associate members about behaviour change in the performing arts, in the light of the ecological crisis and climate change.

This is a complicated matter. In my book Reframing the International. On new ways of working internationally in the arts, I wrote about ‘the gap between thinking and doing’. Most people in the performing arts will be quite aware of the human factor in the climate catastrophe. Still, many find it difficult to imagine how you can match this insight with your practice, in a sector that relies heavily on international mobility.

For this, I referred to the interesting essay by Jeroen Peeters, “Transition exercises for a more sustainable mobility”, which pointed to the tension between personal action space, the responsibilities of the art world as a whole and systemic change.

"The change in behaviour of the few who assume responsibility for working out alternatives is often at odds with the absence of structural change within the sector and society as a whole. A kind of exhaustion looms: your personal carrying capacity is inevitably limited. How strong is the flexitarian all on his own?" (Jeroen Peeters, Transition exercises for a more sustainable mobility)

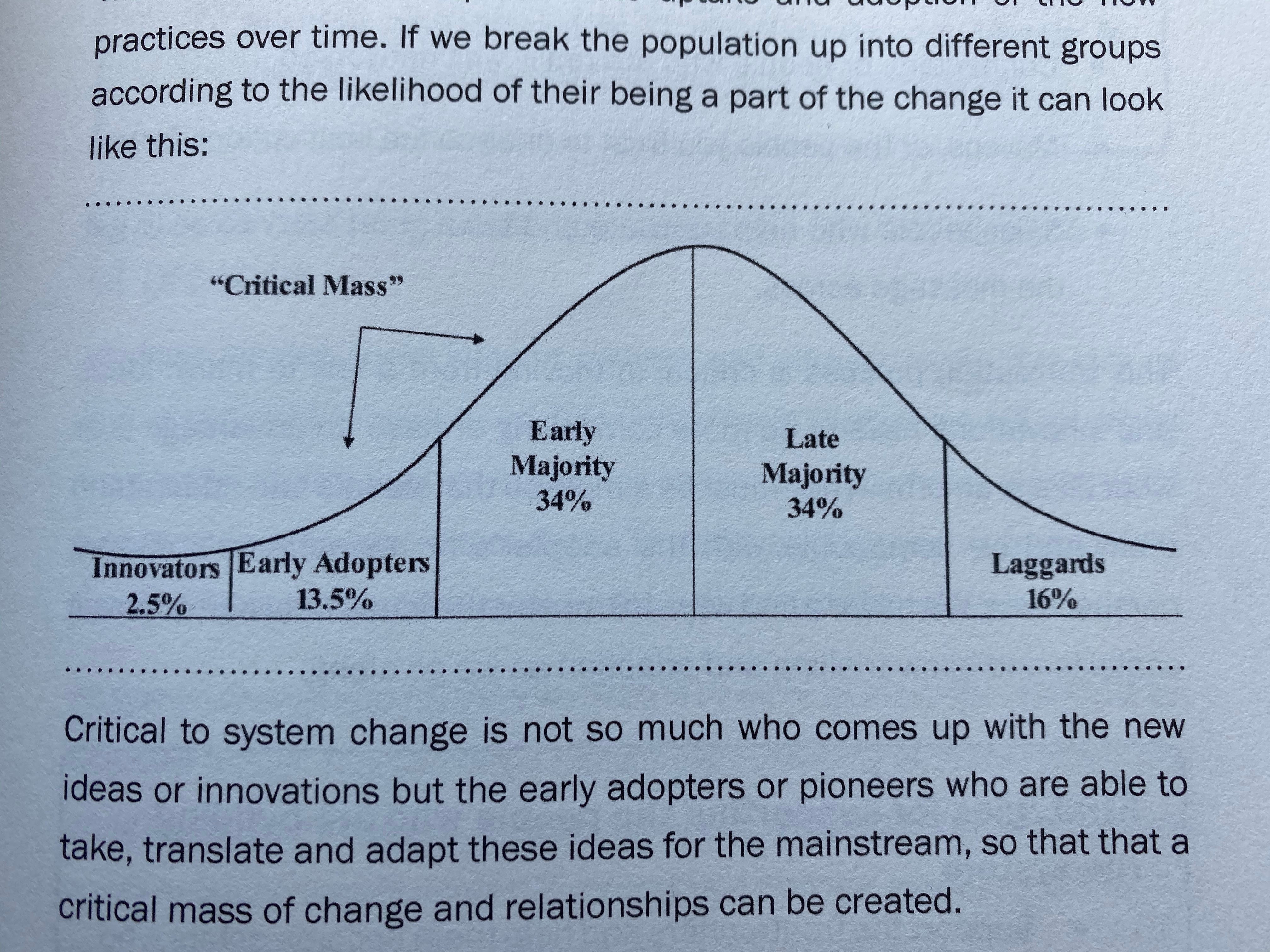

In his article Jeroen talks about his own efforts to travel less and develop alternatives. There are many like him. However, most people in the sector are not. This is not weird. In my intro for the workshop, I showed a graph that I saw in a book by Anna Birney. She remarks that system change does not happen with everybody at the same time:

Where are we now, thinking about ecological behaviour shifts in the performing arts? Certainly there are innovators, maybe some early adopters, but no critical mass. In the quote in the picture, Birney points out that it’s not the innovators, rather the early adopters that might mainstream the innovations and really create critical mass, because of their ability to connect and persuade. To multiply.

That is why this session with the associate members at the IETM could be important, I thought. Of course, it is in the DNA of IETM to connect. The ‘associate members’ present in the session were mostly intermediaries that have funding programmes and regulations. They too can be multipliers.

I pointed out that this gap between thinking and doing can be complicated. For the session I chose to focus on the positive. The aim of the session was to raise awareness and show opportunities to further engage with the topic, to create positive vibe and explore possible approaches in relation to this the central issue: behaviour change with regards to ecological sustainability in the performing arts. That is why we did a session of appreciative interviews.

The participants shared personal success stories about where their behaviour shifted, or the policy of their company changed, for ecological reasons. Three questions were answered. What happened there? What feelings did this provoke? And what were the necessary conditions or resources that allowed this shift to happen?

The stories that the participants came up with, were quite diverse, but as more stories accumulated, some red threads started to appear. These were my learning points of the session:

- Tweaking the schemes. Small changes to subsidy schemes and regulations can have a positive effect. Think about the conditions and the criteria of your funding schemes, someone pointed outn and innovate. for instance touring schemes that actively promote train use or the combination of different activities to have longer tours.

- The importance of ecological education. For some participants, ecological behaviour change started during childhood, through education at home. Can this be learned also later in life? Of course, funding bodies can set up programmes for raising awareness and the sharing of knowledge, but I tend to believe in bullet 3.

- Leading by example, multiplying through inspiration. Behaviour change often happened when a passionate, inspirational person created awareness and gave the good example. The importance of examples, ‘connectors’ and mobilisers, pointed out in Anna Birney’s book, was confirmed in many stories. It can play out on an individuel level, but also on a collective scale (movement design).

- Connect to nature, start at home. Connecting to nature an in personal lives (e.g. gardening) has several effects. Not only does it improves your well-being. It raises awareness about ecological issues, this might change concrete decisions you make in your professional life. Which feedbacks into well-being, because almost everybody testified that a professional practice in tune with your values is empowering.

- Change organisational policies. Make your organisation more ecologically sustainable, e.g. by developing organisational policies for reducing waste, or avoiding the use of plastic. If you’re in a position to do so, this is low hanging fruit. Otherwise, organise a climate strike in your company.

- Greening public space and cultural infrastructure. In some of the stories about behaviour change, space and infrastructure were crucial resources. A square in Utrecht and the front of a culture centre in the UK were changed into a public garden. This had a positive effect on many levels: not only well-being through a better, greener environment. Also social bonds were strengthened, since gardens were taken care of by volunteers and were even part of community arts projects.

- It’s not a question of money, it’s a question of priorities. Some of the policy measures and actions described above required a bigger budget, but not all of them. Some of these ideas were budget-neutral, others were a matter of shifting priorities. So stop wasting time, start loving nature, feel better and save the planet.

This article was originally published on Joris Janssens' blog on the 26th of October 2019. Read the original article.