Willing change in a world of many crises

Ragnhild Freng Dale explores activism in the performing arts and the opportunities this type of theatre opens while looking into different examples of political activism in the arts, with a focus on movements in Northern Norway.

This article was initially commissioned in preparation for the IETM Plenary Meeting in Tromsø, 30 April—3 May 2020, which was cancelled due to the COVID-19 outbreak. The meeting program was planned to discuss, digest, and discover the role of activism in performing arts, the relation between art and politics, and art as protest. These questions remained relevant in times of the pandemic, when IETM organized their Digital Journey to Tromsø to compensate for the canceled Plenary.

What does it mean to talk about theatre, politics, and activism at a time when we all isolate our bodies from those of others? As I’m writing this, the rain is hammering on the window outside my house in southwestern Norway, all my travel plans to meetings and conventions cancelled for the forthcoming months. My mind, which I had thought would vibrate with energy and burning questions about activism and the performing arts, feels terrifyingly blank.

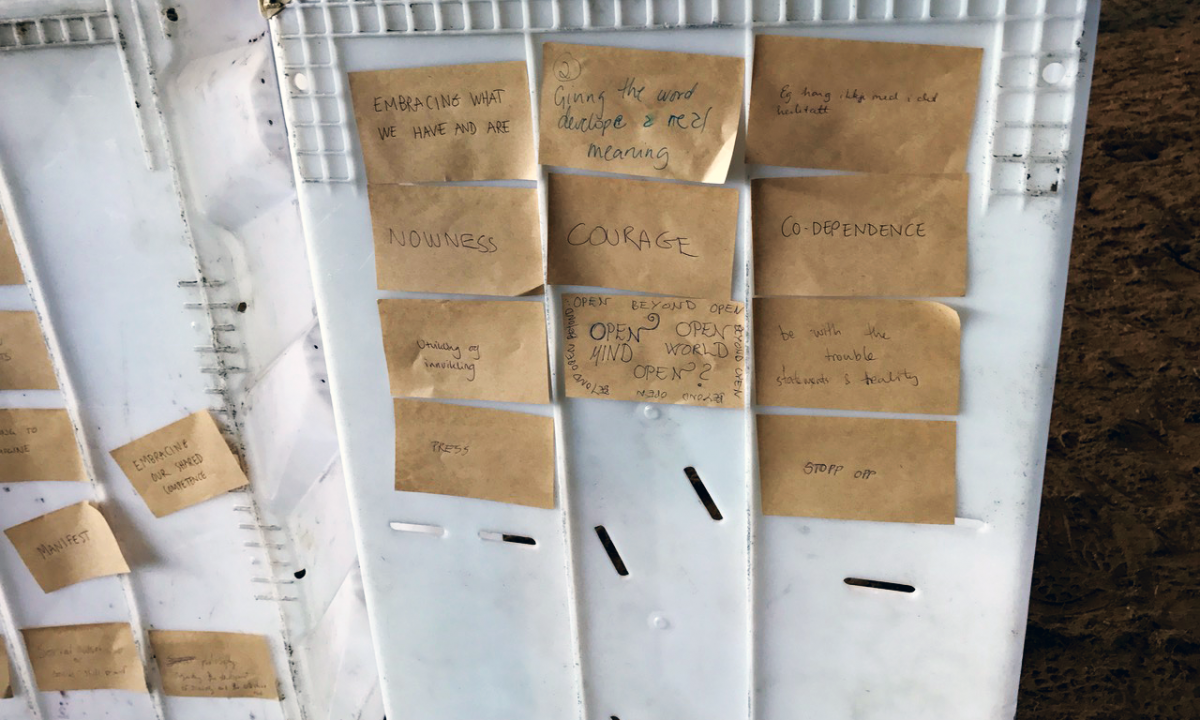

I rewind to 2017, placing myself back on the island city that goes by the name of both Tromsø and Romssa, reflecting on how it is part of both Norway and Sápmi—the Northern Sámi name of the land of the Indigenous Sámi people, which stretches across the borders of what is currently known as Norway, Finland, Sweden, and Russia. I replay the beginning of the annual festival happening there, Vårscenefest, where I was attending a seminar called Agency for De-development in Tromsø. Over the course of two days, it brought together artists, makers, academics, and others and addressed a number of dilemmas, conflicts, priorities, and ways of togetherness between humans and non-humans across the island.

It was the time of year when winter begins to let go into spring, and we crossed Tromsøya on foot before lunch, walking for an hour on snowy roads in bright sunshine. We talked about what development means, about our personal lives and choices, and about our expectations for the days ahead. We ate the most delicious falafel at the market square, then walked to the docks and played with the crates normally used to store fish in, before we had a long and heartwarming conversation inside a cold storage building. We continued similarly the next day, where our conversations centered around fish and petroleum, indigeneity and solidarity, affordances of architecture and the future of the performing arts, as well as that of the city and region itself.

When thinking about theatre and the political, events like these might not be the most obvious. I could have invoked something more spectacular, like BP or not BP, a group of artivists who—in their avowals to kick British Petroleum and their sponsorship money out of institutions like the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) and the British Museum—have invented their own genre of actor-vism. After they jumped the stage before a show at the RSC in 2012 to proclaim their disgust at the sponsorship in Shakespearian verse, they have combined ever-more inventive actions with research into sponsorship ties and solidarity actions with groups that have suffered at the hands of colonialism and looting by the British empire and the oil company in question. Most recently, they managed to pull a full-size Trojan horse into the British Museum’s courtyard and arrange a sleepover inside the museum.

In the same vein we could mention the culture jamming of Yes Men, who bluff their way into corporate conferences and onto national television in ways that seek to expose corporate power with humor and ingenuity. Perhaps their most famous example is when they impersonated a spokesman for Dow Chemicals and claimed full responsibility for the Bhopal disaster live on BBC.

If I wanted to stay geographically in Norway and Sápmi, I could have mentioned the artwork and movement Pile o´Sápmi by the visual artist Máret Ánne Sara, who creates visceral work with reindeer skulls linked to her brother’s fight for the right to maintain his reindeer herd against the unjust regulations of the Norwegian government. With matters concerning the Sámi rarely given attention in national media, Máret Ánne’s visual art is both a powerful expression and a successfully deployed tactic, catching the attention of the majority of society and recasting the narrative in national and international debates. Though not strictly performing arts, her work is a prime example of the political potential of a well-chosen aesthetic with a strong and clear narrative that arises from a specific case, but it also speaks to a bigger issue of the relationship between the Norwegian state and its Indigenous population.

I could also bring up artist Amund Sjølie Sveen’s work Nordting (The Northern Assembly), a show that is part satire, part political intervention, and part performance lecture with a large dose of audience participation thrown in. During the show, audience members cast their vote in response to issues ranging from a sovereign North to control over fish and petroleum resources. Sarcastically critiquing powerful companies and people, the show has received wide popular acclaim and positive reviews, whilst also managing to provoke institutions, politicians, and investors.

But let us return, for a moment, to where we started. As different as all these examples may be from the workshop with the Agency for De-development, which was more centered on opening new perspectives and dialogues through embodied experiences, they share an important commonality: not in the explicitness (or lack thereof) of the political, but in their insistence that an otherwise is possible. As political theorist Chantal Mouffe has put it, all art serves to uphold or challenge the hegemonic order. But the shape of the challenge, I have come to learn, comes in many formats. The shape need not be a revolution; it can also be an exploration of possibilities. In Tromsø, the artists brought us along on such explorations in a way that felt as gentle as it was challenging, invoking thoughts and possibilities I would not have found otherwise.

Can we perhaps call this a move towards utopia? Not as a chimera, but as that other place where we do not (yet) know how things will be. And when we can imagine the glorious possibility of something better than what we currently have, why shouldn’t we?

When talking about politics in theatre, we are really asking what other worlds it makes possible. Not as a specific type of action or outcome, but rather of a prefigurative element—a will to practice different worlds through what artists make, create, and facilitate. They may utilize different techniques, traditions, and methodologies when they create their work, or have different underlying motivations—some do artivism, others call it performance protest, some want to say interventions, others just make art that is important to them with an urgency they need to share. Some are more subtle in their approaches, exploring methodology and their own place as much as willing change on a specific issue. Others deliberately use artistic means to play with what is considered to be the “normal” way of things.

For me, a willingness to seek and create friction against what we take for granted in the everyday, or when the world is in crisis, is what makes a piece of work worth engaging with. Or, as I always ask whenever I encounter someone else’s work: What do the artists want? How are they bringing me, or us, along?

As the measures to stop the spread of COVID-19 have upended and shut down so much of what I hold dear, including the freedom of assemble, the freedom to protest, and the freedom to travel, such an energy is suspended, frozen in its vibration except in the digital realms. It is hard to think about making art and work that changes the world at a time when we are all confined to our homes and our immediate co-dwellers. It is hard to think that we could do these sort of performance interventions, these gatherings in large groups and smaller groups. It is hard to imagine that I will one day walk and talk again with others after sharing a workshop or seminar designed to upend some of our everyday assumptions.

Paradoxically, as I write this in the absence of such possibilities, that absence tells me very strongly what drew me to theatre and the performing arts in the first place: the sense that the otherwise is possible. Everything is not predestined, and this isolation will not last forever. The performing arts, in confinement and after, need to keep poking new holes and open new spaces in the commonsense order of things, tearing and sculpting possibilities in the social fabric. If we make work that can imagine otherwise, that change is already on its way.

This article was originally published on Howlround on the 5th of May 2020. Read the original article.